2017: Brant Houston and Nils Mulvad back in the garden in Risskov, Aarhus, where they decided in the year 2000 to hold the first global conference on investigative and computer-assisted journalism. Photo: Lone Hougaard.

Read Nils Mulvad’s personal account of DICAR’s history. The center was founded 25 years ago in 1999 and closed in 2007.

During its existence, DICAR was at the forefront of developing data journalism in Denmark. The center was responsible for the practical execution of the first two global conferences in investigative journalism and played a central role in forming the worldwide network, the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN).

DICAR’s legacy extends many years beyond its closure.

How could a man from Aarhus help establish the global network for investigative journalism and promote data journalism? Why did things unfold as they did? Let me share my version of the events from that time, with DICAR at the center, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.

Background and First Steps

In the fall of 1989, as a newly graduated journalist, I participated in the founding meeting of the Association for Investigative Journalism (FUJ). In the early years, there were several initiatives and meetings within the association focused on IT and investigative journalism.

At that time, I was 34 years old and had started journalism relatively late. I was much better at math and chemistry and had studied biochemistry at the University of Copenhagen, while languages were not my strong suit. However, my curiosity about people and the reasons behind their actions and beliefs led me to switch to journalism, particularly investigative journalism.

I got my first job at Computerworld in the summer of 1989, eager to learn about understanding and using computers. Within FUJ, I helped organize a meeting at Siemens in Denmark about the impact of IT on society.

I contributed to writing responses regarding editorial databases for a legislative proposal on internal editorial databases, which was passed and is still in effect. I also collaborated with the Danish DIANE Center to produce a brochure about databases in journalism and organized training sessions on database usage, as well as a meeting in Aarhus about electronic access to documents in collaboration with the Ministry of Finance.

Journalist Henrik Kaufholz from Politiken was a major driving force in the association’s early years. When he became a correspondent in Germany, activity declined significantly, and a couple of annual seminars were canceled.

Together with freelance journalists Lars Møller and Morten Friis Jørgensen, I attempted to revive the association, with assistance from the Danish School of Journalism, by organizing an annual seminar in November 1995 at the school in Aarhus. I had moved to a small town, Rostved, about 20 km outside Aarhus in 1991.

By November 1995, I had worked at the Danish School of Journalism for a couple of years as a lecturer, and since August 1995, I had been employed at the IT desk at Morgenavisen Jyllands-Posten.

Confrontations and New Directions

Following the annual seminar, Morten Friis Jørgensen became chair, but within a few months, he was removed from the executive committee by two other members, Peter Hjorth (editor of Sygeplejersken) and Bente Troense (editor at TV2), after inquiries from the Danish School of Journalism and Jyllands-Posten, both stating they could not collaborate with Morten Friis Jørgensen. This conflict significantly impacted future developments.

In the spring of 1996, Mogens Møller Olesen from the Journalistic Continuing Education, Flemming Svith, and I attended a boot camp in Columbia, Missouri, USA, to learn data journalism at the National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (NICAR). Flemming Svith was my colleague at Jyllands-Posten at that time.

Mogens Møller Olesen and I used our newly acquired skills for a short training session at the FUJ conference in June 1996. After that conference, our efforts faced criticism. The then-executive committee of FUJ, led by Peter Hjorth, informed us that they did not wish to spend time on data journalism in the future, as they felt it did not align with investigative journalism.

To avoid further conflict after the fallout with Morten Friis Jørgensen and the new executive committee over data journalism, a group of IT-interested journalists started the Association for Computer-Assisted Journalism (FCJ) in the summer of 1997.

The idea emerged during the first Danish continuing education course in data journalism in June 1997, held over five days at the School of Journalism. I had received approval from the school to invite two guest lecturers from NICAR: director Brant Houston and staff member Gwen Carleton, who was married to a Dane and spoke some Danish. Both had taught at boot camps in the USA the previous year.

The course revealed a foundation for advancing data journalism through a new association. A phone call to Mogens Møller Olesen confirmed his interest in the idea. We initiated the formalities by drafting bylaws and calling for a general assembly. FCJ was founded, with Tommy Kaas as chair, then deputy editor at De Tre Stiftstidende and Jyske Vestkysten’s joint office in Copenhagen.

The first snapshot of DICAR’s website can be found on Archive.org from October 8, 1999.

Establishment of DICAR

In the spring of 1998, I realized that alongside FCJ, we needed an executing organization modeled after the USA, where the American association Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) had an agreement with the University of Missouri to host NICAR.

We could achieve this by having FCJ enter an agreement with the Danish School of Journalism, as it was called then. The idea received support from FCJ and from a collaboration on electronic access to documents that I had worked on for several years with then-department head Knud Aage Frøbert and rector Kim Minke—both from the Danish School of Journalism.

We formed a working group to prepare for the establishment of the Danish Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting (DICAR). Data was to be used as a tool in journalism to improve research and communication. We aimed to create teaching materials, courses, toolkits, databases, and much more. From FCJ, this included Tommy Kaas, Flemming Svith, and me. Knud Aage Frøbert and Kim Minke were also solid supporters throughout many activities.

At that time, Knud Aage Frøbert was managing the Press Emergency Service, established on the initiative of journalists Ole Skydt and Jan Kaare from Danish Journalists’ Union, and they also joined the working group. With Knud Aage Frøbert’s leadership, we formulated bylaws, a collaboration agreement with DJH, and established that our work would consist of three pillars: data journalism, electronic access to documents, and mailing lists.

I was initially a bit nervous about Knud Aage Frøbert’s reaction to the idea of DICAR. Would he agree to establish a proper institute? Or would he oppose mixing electronic access to documents with data journalism? Fortunately, he was enthusiastic and instrumental in shaping the initiative. He struggled with IT, but he had no trouble understanding its importance and the legal implications.

At FCJ’s general assembly in 1999, we received the green light to implement the plan. DICAR’s first board consisted of the same seven people from the working group.

First-Hand Sources of Events

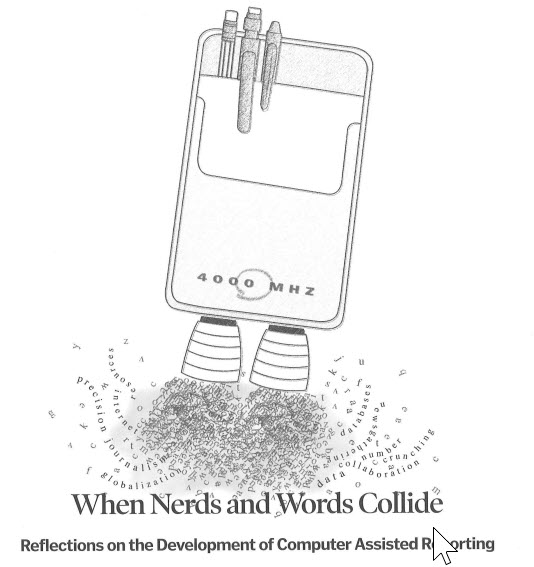

An intriguing source for understanding the background of the plans for DICAR can be found in my contribution to a conference at the renowned American institute Poynter in January 1999—10 years after the first American conference on computer-assisted reporting. Poynter aimed to gather experiences and discuss possible plans for the next decade. The institute gathered 20 of the most recognized American data journalists and editors at the time, including the luminary Phil Meyer, regarded as the creator of the analytical and scientific approach to journalism. Additionally, three non-Americans were present: Mexican Pedro Enrique Armendares, Dutch Peter J. Verwey, and myself.

The frontpage of the collection of contribution to the Poynter-seminar in January 1999.

My contribution, titled “Stories are the Proof,” is included in the text collection “When Words and Nerds Collide.” It discusses how, in Denmark, we prioritized writing good investigative stories using data to demonstrate that the method of data journalism worked effectively and created new, exciting stories, such as the revelations about the extensive side jobs of Supreme Court judges. The piece also outlines where the new DICAR would focus its efforts.

First paragraph in Tommy Kaas’ annual report in year 2000.

Another valuable source for the plans can be found in Tommy Kaas’ annual report to FCJ’s general assembly in 2000, where he describes the process of establishing DICAR.

The Dark Chapter: Mailing Lists

The mailing lists represent a dark chapter. A few municipalities created an overview of daily mail for local media. The idea was to encourage more municipalities to adopt this practice and shift these lists online for easy access to potentially important stories.

In 1998, Ole Skydt and I toured municipalities in Funen, including Ringe and Nyborg, to encourage them to publish electronic mailing lists online. Ringe municipality was the first to do so, launching its mailing list online in 1998, followed by a surge of municipalities and regions adopting electronic mailing lists over the next few years. We held several conferences on the subject, confident that it would gain traction.

During our 1998 tour, I bought a couple of bottles of particularly good pirate port wine at Aldi in Svendborg and agreed with Ole Skydt that we would drink one together when all municipalities in Denmark had implemented electronic mailing lists.

The mailing lists primarily contained information about numerous important local conflicts, particularly in the Technical Administration’s various construction cases. These points sparked many concrete local stories. In fact, the mailing lists also led to fairer media coverage of various interests. In places without mailing lists, such stories often ended with criticism of the municipality or region. At its peak, about a third of municipalities and four regions had mailing lists.

With the structural reform that took effect on January 1, 2007, the decline of electronic mailing lists began. It seemed that openness and democracy receded in favor of efficient administration and governance in municipalities and the new regions.

Today, the idea of electronic mailing lists is completely dead in Denmark, while in Norway, it remains a central and successful form of transparency.

The good bottle of pirate port wine still sits at the back of my liquor cabinet.

The pirate port wine, purchased in 1998 in Svendborg, was intended for the celebration of electronic mailing lists in all municipalities. It never came to fruition, and the bottle was brought out for a photo session for DICAR’s anniversary, still unopened and now over 100 years old. After the photo, the bottle returned to the back of the liquor cabinet. Photo: Nils Mulvad.

First Global Conference in 2001

When Brant Houston from IRE and NICAR visited Denmark in the spring of 2000 for our annual CAR day—a mini CAR conference we held every year at the School of Journalism—he suggested that we hold a global conference. The focus would be on both investigative and computer-assisted journalism. It couldn’t be much different from holding a Danish conference, he said. Hesitantly, I agreed and got to work.

I reached out to outgoing TV2 director Jørgen Flindt Pedersen, who had just taken over as FUJ chair from Peter Hjorth at FUJ’s annual meeting in April. My hope was that the IT-hostile stance in FUJ could be set aside, and that together we could organize the global conference the following year.

Jørgen Flindt Pedersen was on board.

Meanwhile, FCJ and DICAR had received funding from the Jyllands-Posten Foundation to translate teaching materials into English and had collaborated with American instructors at the Netmedia conference in London. The previous year, we had received support from the Press Educational Fund for two projects: 50,000 DKK for a combined research and education project on developing electronic toolkits, and 60,000 DKK for a research project on building a database library for the media.

Now we aimed for larger grants from Digital North Jutland and the EU’s Social Fund.

DICAR also hired its first real part-time employee, Solveig Schmidt, in 2002. She was a former professional secretary in the journalists’ union and took on the responsibility for DICAR’s courses. From the fall of 2002, DICAR had an intern from political science who helped explore funding sources—both to finance the global conference and to secure grants for our many plans with DICAR.

I also went part-time at Jyllands-Posten at the end of 2002 to have time to organize the global conference. One of the major questions during the planning of the upcoming global conference in 2001 was where and when to hold it. I had written about hotel king Henning Remmen, the owner of Hotel D’Angleterre, in Jyllands-Posten. He offered two great pieces of advice: first, to schedule the event for the last week of April when the weather is often quite nice, but prices haven’t gone up yet; and second, to purchase the conference as day packages at D’Angleterre, where we could get coffee, tea, water, lunch, and conference rooms for nearly 400 kroner per participant. The price was on par with other training venues, but the quality was much higher, and the unique location attracted foreign guests—and probably Danish ones, too.

DICAR Becomes a Commercial Association

At the global conference in 2001, time was set aside to merge the two associations, FCJ and FUJ. It was a complicated plan involving a general assembly first in one association, then the other, and finally in the combined association. Everything was very close to going wrong. Shortly before the meeting, FUJ had cold feet about DICAR. The reasoning was that it was too large and financially unmanageable.

Thus, FUJ wanted to merge with FCJ but did not want DICAR to be part of the equation, while we in FCJ saw DICAR as the crucial operational part with employees and a larger budget. We were very close to canceling the merger and continuing the existing structure with FCJ, DICAR, and the School of Journalism—without FUJ.

Instead of calling off the merger, the boards of FCJ and DICAR found another way forward. We agreed to merge FCJ with FUJ and initially sidelined DICAR, where only the board was responsible for the organization. This could work for a period, but it wouldn’t be a sustainable structure for larger funding grants, which require an association or similar as the overarching responsible entity.

During the fall of 2001, we established DICAR as a commercial association, with members being institutions and organizations, including FUJ, the Danish Journalists’ Union, the Danish Media Association, and a range of Danish media outlets. With the commercial association in place, we could realize the plans for funding—first from Digital North Jutland and shortly thereafter from the EU’s Social Fund, with a total grant of about five million kroner.

We preferred the model from the USA, where the investigative association has an agreement with a university and operates NICAR from there. However, we assessed that it could also work in the way that resulted now. We had successfully merged the two associations, FCJ and FUJ, and thus there was no longer a formal disagreement about whether data journalism was a method in investigative journalism.

At the same time, we had established a good and responsible structure for DICAR.

Farewell to Jyllands-Posten – Hello to Full-Time Positions at DICAR

As mentioned, I had been working part-time at Jyllands-Posten since the fall of 2000 to prepare for the global conference. When we received confirmation of the grant from Digital North Jutland, I resigned from my position and started full-time at the School of Journalism in November 2001, where I worked three-quarters of my time as director of DICAR. Physically, DICAR was located at the School of Journalism, and there was an agreement between DICAR and DJH regarding my employment.

Shortly thereafter, both Tommy Kaas and then Flemming Svith accepted full-time positions at DICAR. This way, we gathered the most experienced and active users of data journalism in Denmark at DICAR. Flemming Svith was the structured one who had developed the systematics of our teaching materials and methods. Tommy Kaas was the search and mapping expert, who was also the most pedagogical instructor.

We hired Lisbeth Mogensen as our secretary. Later, Michael Holm, Kresten Roland Johansen, Lars Aarup, and IT developer Kim Stenbryggen joined, along with many political science students who came through the system.

I stepped down as chair of the board in the new DICAR, and both Flemming and Tommy also left the board as we became employed at the center. Bruno Ingemann, who at that time was deputy head at DR Nordjylland, took over as chair of the board in DICAR.

2023: Brant Houston and Nils Mulvad celebrates 27 years of friendship in Pacific Grove in California. Photo: Lone Hougaard.

Global Network Founded in 2003

At the 2001 conference, there was significant interest among participants for more collaboration and more conferences. You could sense it in the lively discussions at the lunch tables, in direct requests, and in the debate at the end of the conference. After a brief and perhaps hasty consideration, I promised from the podium that DICAR would handle the coordinating work for the next global conference in Copenhagen, also at Hotel D’Angleterre, but not until two years later, in 2003. I justified the two-year interval by saying we could not manage it with only a year of planning this time.

Thus, DICAR, along with American IRE and FUJ, would be responsible for the 2003 conference. The 2003 conference faced a particularly unique challenge: a decline in the number of participants, likely due to the Iraq War beginning shortly before the conference. The financial situation was quite poor, and it really pointed towards canceling, which would have been detrimental for many years to come.

I initiated a significant cost-saving round around the conference. The most effective measure was with the billing to D’Angleterre. In relation to D’Angleterre, we measured the number of participants per lunch guest as the basis for billing. Therefore, it was important to reduce that number. A lot! I checked participants’ wishes for lunch. I then reduced that number by an additional 20 percent and ended up ordering the conference for 200 guests each of the four days, even though there were actually 300 participants plus staff. This one step saved about 120,000 kroner.

The staff had to constantly count how many were actually present for lunch and only go in to eat themselves if we were sure we kept the total number under 200. On one of the four days, we exceeded the number by three or four, but otherwise, we adhered to the savings plan and secured a significant reduction in the deficit. However, we could not completely avoid a deficit, which ultimately was divided among the three organizers with about 50,000 kroner each.

At the 2003 conference, Brant Houston and I founded the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN). The primary aim of the network at that time was to create a background group of relevant associations and organizations to provide input on the content of the conferences, such as topics, panels, and speakers.

Since then, the network has held a global conference approximately every two years. In the early years, the network was managed by Brant Houston and me, while a national organization was responsible for each conference, which in subsequent years was held in Amsterdam (2005), Toronto (2007), Lillehammer (2008), Geneva (2009), and Kyiv (2011). At the Kyiv conference, we managed to establish a proper secretariat under David Kaplan’s leadership, and the following year, we established a board for the network.

Two good sources about the founding of the global network are David Kaplan’s “20 Years On, A Global Network for the World’s Investigative Journalists,” which describes the network’s beginnings, and a more personal perspective in the interview with Brant and me in the Swedish magazine Scoop: “Vännerna som grundade GIJC,” leading up to the Gothenburg conference in 2023.

For my work founding and running GIJN together with Brant Houston in the early years, I received the organization’s first “The GIJN Leadership Award” in 2017.

Establishment of Scoop – Investigative Journalism in Southeastern Europe and Ukraine

Journalist Martin Breum from International Media Support in Denmark, established to support media in vulnerable areas, approached me in 2002 with the idea of creating a support function for investigative journalism in Ukraine and Southeastern Europe. He had received feedback from Ukraine that their courses in investigative journalism were good, but participants also wanted to try their hand at investigative journalism in practice.

At the School of Journalism, I had conducted a series of courses in data journalism in Southeastern Europe and had identified three potential country coordinators for the new project during these trips and through correspondence. They were journalists Milorad Ivanovic from Serbia, Stefan Candea from Romania, and Zoia Dimitrova from Bulgaria, while Martin Breum maintained close contact with Valentyna Telychenko and Oleg Khomenok from Ukraine. Martin Breum and I wrote a grant application to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and secured the initiative within FUJ.

The participants from the training in Southeastern Europe made up a large group of attendees at the global conferences, and several went on to play significant roles in the development of the global network and other projects that followed from what was initiated back then.

Henrik Kaufholz returned to Denmark in 2002 after serving as Politiken’s correspondent in Germany and later in Russia for several years. Tommy Kaas and I persuaded him at a meeting in Politiken’s canteen to become the coordinator for Scoop.

Henrik Kaufholz quickly embraced the idea and subsequently led the Scoop project, which has funded a series of excellent investigative journalism projects. Today, Scoop has closed, but especially in Ukraine, the Scoop project has had a significant impact, as Oleg Khomenok has played a crucial role in the development of the country’s investigative journalism for over 20 years.

The First Major Breakthrough for Data Access – School Exit Grades in 2001

The first major breakthrough in obtaining data through access to information in Denmark came in November 2001, namely the exit grades of primary schools. I obtained data for all schools in the country and could compare the results across the nation. Since then, a wealth of data has been released with great stories following, for example, Tommy Kaas’s investigation into library funding.

Before that, many of our data stories were based on building our own databases, such as a major series of articles on Supreme Court judges’ side jobs in Jyllands-Posten in 1998.

Farmsubsidy.org – Prices and Dataharvest

In addition to contributing to the many data stories in the media and teaching, DICAR was also central in many access-to-information cases regarding environmental data. The most well-known is probably the case concerning agricultural subsidies, where journalist Kjeld Hansen and I successfully obtained data in 2004 about all Danish recipients of the EU’s agricultural support.

I was about to give up on the case because the ombudsman had rejected our request three times. The ministry explained to the ombudsman that the vast amount of data did not exist in an IT system, and therefore they could not provide the file we requested with the data.

However, I persisted, and in the end, it turned out that the data was indeed on a file, and we received it. The then Minister of Food, Marian Fischer Boel (V), subsequently had to go to the parliamentary podium and apologize for misleading the Folketing’s Ombudsman.

The following year, Jack Thurston succeeded in obtaining agricultural subsidy data in the UK, after which Jack Thurston and I founded Farmsubsidy.org with the aim of obtaining agricultural subsidy data across the EU through collaboration between journalists and organizations in all EU member states. We quickly brought Danish journalist Brigitte Alfter onto the project to coordinate journalists in other countries.

Farmsubsidy.org comprised a mixed bag of organizations and individuals. There were individuals in one country, a scientific institute in France, various non-profit organizations that were not media, journalists from media, and us at DICAR. The goal of the collaboration was to gather as much information as possible about agricultural subsidies and publish it, after which people could use it for their own purposes.

The EU’s Social Fund financed the central part of the project in the early years as part of DICAR’s work, after which the American Hewlett Foundation took over. The central tasks included scraping, checking, cleaning, and publishing data, managing the website, and organizing our annual meetings.

In 2007, the meeting was in Budapest, in 2008 in London, after which we moved it to Brussels and called it Data Harvest.

We quickly achieved breakthrough after breakthrough, and in 2006, I was awarded the title of European Journalist of the Year by European Voice, owned by the Economist Group.

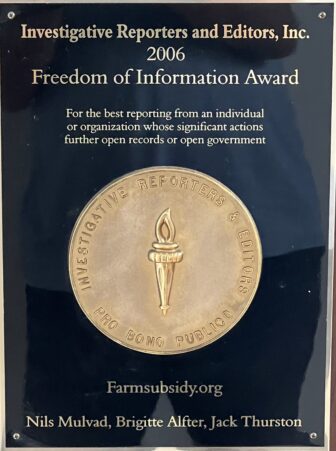

At the IRE conference in June 2007, Jack Thurston, Brigitte Alfter, and I received an IRE Award for Freedom of Information based on the breakthrough in transparency regarding agricultural subsidies, which at that time constituted about half of the EU’s total budget.

We held our annual meetings in May. Jack and I humorously called them the Data Harvest Festival because we were harvesting data—either through scraping or other tricks. Afterwards, we structured and analyzed the data to uncover good stories in each country.

Data Harvest evolved into a conference on all forms of investigative and computer-assisted journalism in Europe from 2012 onwards, and it continues to thrive today within the organization Arena, led by Brigitte Alfter, still holding annual conferences in May.

The End of DICAR

The grants from Digital North Jutland and the EU’s Social Fund expired at the end of 2003, but we managed to renew the grant from the Social Fund for the years 2004-2006. Unfortunately, we could not secure further funding and had no luck obtaining grants from other sources, so we regrettably had to close DICAR at the end of 2006.

Tommy Kaas and I decided to continue the activities we could finance through commercial sales in the company Kaas & Mulvad, which we started on January 1, 2007.

The formal closure of DICAR occurred at the general assembly in May 2007, where the accounts were approved. The surplus was distributed to various good causes. The Social Fund required that all accounting materials, including time registrations for all participating journalists from the media, be kept until the end of 2012 in case of an extraordinary audit from the EU. Kresten Roland Johansen and I packed everything into moving boxes, which were stored in the School of Journalism’s archive in the basement of Olof Palmes Alle. The extraordinary audit never occurred—a chapter was closed.

Solveig Schmidt left DICAR when we received the large grants in 2001. She continued as a lecturer at the School of Journalism and was responsible for the entrance exam, among other things.

Flemming Svith continued at the School of Journalism after DICAR’s closure, earned a PhD, and was employed in a research position. Kresten Johansen was also hired at the school—initially in the international department, now as a lecturer. Kim Stenbryggen was hired in the school’s IT department, while Michael Holm left DICAR the year before to work first in media and later in communication. Lars Aarup became a long-term analysis chief at Coop.

Bruno Ingemann, the chairman of DICAR, is now the head of the Investigative Center in Denmark.

The Name DICAR – What Does It Represent?

When we founded DICAR in 1999, we wanted a name that clearly and precisely described our purpose.

We chose the term “Danish Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting.” This way, we hoped everyone would understand that it was about the use of computers and data processing in journalism. The American NICAR – National Institute for Computer-Assisted Reporting inspired us to the name.

We shortened it to the catchy “DICAR,” which gradually became well-known among Danish journalists. Many referred to us simply as “Dicar” with slightly different pronunciations.

After a few years, we wanted to change the name to something more representative of our expanded activities. This was especially pushed by my colleague Flemming Svith. At his suggestion, we changed the designation in the mid-2000s to “Danish International Center for Analytical Reporting,” which could still be abbreviated to DICAR, and which had become synonymous with the use of data in Danish journalism.

In many ways, “DICAR” became a trademark that clearly marked the pioneering work that the institute undertook for several years.

Later, the term Computer-Assisted Reporting faded and was replaced by data journalism and, in some cases, data-driven journalism. Data-driven journalism signals data as the driving force, whereas data, in my view, is just one of the tools alongside others like interviews, observations, and, in the past, paper records. In many cases, there has been too little journalism and too much data in data-driven journalism. Therefore, I prefer the term datajournalism.

Why Was It Successful?

Well…

Luck.

We had gathered some of the best data journalists in Europe at that time, each with different strengths that complemented each other.

Stubbornness.

Financial common sense.

And surely many other reasons.

En smuk og lærerig historie Nils! Og et kæmpearbejde. Super!